All lovers are not poets but all poets are lovers, in one way or the other. If poetry is a love affair with life, which it is, then the poets must have a beloved. In some cases, poets have had more beloveds than one. This made them and their poetry amazingly curious and curiously amazing. Poetic Soul of Universe is about poetry, quotes, life of poets, writers and stories of love.

Monday, 18 May 2020

بازیچۂ اطفال ہے دنیا مرے آگے

Sunday, 17 May 2020

Ishq-e-Meer Taqi Meer (1723-1810)

|

From chronicling the day-to-day experiences of life to exploring

issues in philosophy, Meer’s poetry touches upon almost every aspect of being.

When it comes to describing the matters of love, he stands unparalleled. It is

said that Meer used to go wild at the sight of the moon, as he had an illusion

that face of his separated beloved was reflected in the moon. As Ahmad Faraz

has aptly put:

Aashiqi mein Meer jaise khwaab mat dekha karo

Baawle hojaaoge mahtaab mat dekha karo

Here are some soulful couplets of Meer

where he defines love.

Love is beloved, love is lover

Love, in sum, has fallen for love

Love, oh Meer is but a heavy stone

Too burdening for your weakened bone

Where to find the wandering lovers, to the wind I asked

A handful of dust in the breeze did it cast

In the beginning, a burning flame in love I was

At the end, only a handful of dust I am

Saturday, 16 May 2020

Love-life of Sadat Hasan Manto

Can love

stay away from lust and be love still? Love is labyrinthine; it is both

intricate and tricky. Poets and writers have loved in ways unusual. This makes

them different. Sadat Hasan Manto too loved but in a way that was mysterious

but real. This is what makes this iconic literary figure worth a thought and

worthy of respect. Instead of writing about his love, let us look at how

he related his unusual story about a shepherdess called Wazir Begum. Lovingly,

he chose to call him Begu. He met her in the tranquil and serene climes of

Batote near Jammu, where he spent some time to treat his tuberculosis. Manto

wrote:

‘She was young. Her nose was straight and finely chiselled like a

pencil which I am using to write these lines. Her eyes… I’ve hardly ever seen

any others like those of her. All the profundity of that hilly region had found

its home into them. Her eyebrows were thick and long. When she passed me by, it

seemed as if a quivering ray of sun got entangled in her eyelashes. Her breast

was broad and healthy. Her youth breathed there. Her shoulders were broad, arms

roundish and almost well developed. There were long silver earrings in her

earlobes. Her hair was parted from the middle and tied up like that of the

village women. This gave her face a unique integrity.

I don’t remember how long I kept on looking at

her; I only remember I had suddenly found my breast filled with music…Her

breast was throbbing like water in a fountain. My heart too throbbed by my

side…’

Years later, Manto and Ismat Chugtai happened

to talk about love. Chughtai has narrated one of her conversations with Manto:

He said, “What’s love after all? I love my zari shoes. Rafiq loves

his fifth wife, so what?”

“I mean the kind of love when a young male falls for a youthful lass”.

“Yes, I got it, Manto said to himself, looking for something deeper into

the hazy past.

“There was a shepherdess in Kashmir…”

“Then? I nodded like a listener of a dastan.

“Nothing,” he suddenly got conscious in his defence.

“You tell all dirty stories to me but you are getting shy today”.

”Who is getting shy?” he betrayed his shyness while saying this.

With great difficulty, he could say this:

“When she would lift her stick to lead her cattle, her white elbow would

show up. I was a little unwell; I used to carry a blanket and go up the hill

and lie down there. With bated breath, I used to wait for her to lift her hand

and let her sleeves go up to show her white elbow”.

“Elbow?” I asked in amazement.

“Yes, I didn’t see any part of her body except her elbow. She used to wear

loose clothes. One could not see any curve of her body. On every movement of

her body, my eyes craved to have a glimpse of her elbow’.

“What happened then?”

“Then one day, as I lay on my blanket, she

came and sat at some distance from me. She was trying to hide something in her

collar. When I asked her to show me what she was trying to hide, her face

turned pink. She did not speak a word. I got stubborn. I wouldn’t let you go, I

said, unless you show me what was that you were trying to hide. She turned almost

tearful but I had chosen to be stubborn. After a lot of pestering, she opened

up her fist to me and hid her face between her knees. What I saw in her palm

was a cube of mishri shining bright like a piece of ice.

“What did you do then?”

“I kept on looking at that. Then she went deep into thinking”.

“Then?”

“Then she stood up and ran away. After running a little distance, she came

back, put that mishri cube in my lap and disappeared from my sight. That cube

kept lying in my shirt pocket for a long time. Then I put it in a drawer. A

little later, the ants consumed it”.

“And that girl?”

“Which girl?” he wondered.

“The one who gave you the mishri cube”.

“I did not see her after that”.

“How insipid was your love; I expected a blazing love story,” irritated, I

said in disappointment.

“Not insipid at all,” Manto said as if quarrelling with me.

“Total rubbish, third rate, pathetic love,” I said, “ you came back with a

mishri cube, as if you did some kind of a wonder”.

“Then what do you think I should have done? Slept with her? Leave a bastard puppy in her lap and brag later?” he uttered in anger.

This was

Manto, the author of several controversial stories, who was castigated for

being a pornographic writer. He was indeed a pious soul, an unsullied being by

his head and heart. His friend, Abu Said Qureshi, wrote that whenever we chose

to be naughty with him, we mentioned Begu. This irritated him no end. He hated

the word ‘ishq’ for he knew that not many people would respect its purity.

Manto lived with his memories of Begu all his life. His love was atypical; his

beloved angelic; a holy treasure for life. She was neither a figment of Manto’s

imagination, nor his fantasy; she was real as a real being could be —made of

flesh and blood who could put him to a tough test. He helped her know the

difference between lust and love. Manto wrote once:

‘I often remember her. When going away from me, the tears in her ever-smiling eyes said that she had been quite impressed by my emotions towards her. It appeared that a thin ray of real love had entered the dark recesses of her heart. ..I wish I could take Wazir to the lofty heights of love. Who knows but this girl from the hills could have brought me that precious gift for which my youth has been lazily dreaming while moving towards the impending old age.’

Manto met

many gorgeous and polished women in the Bombay film industry. He could not find

one who could match Begu. He lived a life struggling to discover beauty and

innocence that could possibly be found in dreams alone. Indeed, Begu was more

of a dream for him than a reality. He lived a life in subterfuge, wrote of its

ugliness with a natural flow only to underline that a life full of love is a

distant dream, as Begu was for him.

Friday, 15 May 2020

Love-life of Jigar Moradabadi

Love-life of Sahir Ludhianavi

Sahir was passionate about life, as he was about love. Some of his lady-loves were illusory; others were real but in both he remained a deeply aspirational character. Like an innocent human creature, he used to be fascinated by beauteous beings. Like a guileless guy, he used to find his pleasure in waiting for love to engulf him like magic. Like a naïve romantic, he used to be overwhelmed with a little response from the other side and would hurry to share its ecstasies with friends.

Sahir’s first fascination, which soon grew into love, was for a class fellow called Prem Chaudhari. Both of them studied at Government College in Ludhiana. He talked heroically about finding Prem and boasted that she too loved him as much. Naturally, this became a talking point both in and outside the college. This was also the time when he had started writing poems and making some kind of a name for himself as a typical poet of romance and radical ideas. Prem hailed from an affluent but traditional family where the possibility of such a relationship could not be tolerated. Sahir is said to have wandered at all such places in Ludhiana where she could possibly be seen. Unable to find her around, he even went to her village once where she had gone to stay for a while. When a wandering Sahir reached her home, his roving eyes spotted her walking on the terrace. Prem also saw her but got terribly upset. She feared that if he was found roaming around, he would be treated very severely by her family members. She sent him a message to leave instantly lest he should be put to pain. He returned a forlorn lover but kept pining for her. Soon after that, he got to know that Prem was suffering from tuberculosis. This worried him badly. Much time had not passed before the disease claimed Prem’s life. On getting to know this, Sahir broke totally. After her last rites, he wrote a moving poem “Marghat ki Sarzameen” in memory of his first love where these lines appeared:

Time moved on the way it does and helped Sahir achieve reconciliation with his fate. As he joined life once again, he came across Isher Kaur this time. Both of them idolised each other. This made him take pride in himself and talk about her with pleasure to everyone he knew and cared for. Too deep in his love for her, he remained impatient day and night to meet her. His impatience broke all bounds once. He made an effort to steal a glimpse of Isher and be with her for a while. He went to the college and reached the girls’ lounge where Isher was supposed to be. As ill luck would have it, he was caught by the principal who reached there on getting information about Sahir’s presence near the lounge. He was caught and expelled from the college. As it would appear, Isher could not bring him as many moments of fulfilment as she brought of suffering. On the surface, their story appeared to reach its end but it was not really so. As love does not really die, and as luck would have it, he came to know about her presence in Bombay where she lived with her husband and kids. Sahir too had shifted to Bombay by that time. He found out her whereabouts and reached her home. Soon, he started frequenting her place. This irked her husband. One day, Isher’s husband took him in his car to a far off place and warned him rather severely about his behaviour and unacceptable relationship with Isher. Sahir thought it was time for him to end his misadventure then and there itself. Both Isher and Sahir felt helpless as they had felt earlier. Sahir is said to have written a poem on seeing her sad once. The poem called “Kisi ko Udaas Dekh Kar” had these lines:

Another story of Sahir’s romance that became rather scandalous concerned his stormy relationship with Amrita Pritam. She was a poet and writer, and also a connoisseur of art and Urdu poetry which brought her close to Sahir. Unlike his other real or imaginary love affairs that Sahir used to propagate himself, it was Amrita this time who talked about her strange relationship with him. She even chose to come out with her story in her autobiographical book Raseedi Ticket, and other writings as well. The kind of curious relationship that Sahir and Amrita shared with each other was destined to come to a natural end. Amrita had her own life with Imroz but she was entirely honest in saying that Sahir was her dream but Imroz was her reality. When separated from Amrita finally after a session of drinks, Sahir wrote some of the most moving lines for her:

After Amrita, Sahir met another writer Khadija Mastoor who infatuated him. Their relationship matured to the extent that it could have led to their wedding but that too was not to be. Certain differences between the guardians of the two homes created hurdles in their way. As the coming together of the two could not materialise, the way to make another romantic move was open for Sahir.

Sahir had made a name for himself as a poet rather early. With each passing day, he was getting the limelight. It was then that a film magazine published Madhubala’s image on the cover page with Sahir’s collection of poems Talkhiyaan in her hand. This was enough to inflame Sahir’s imagination and help him start dreaming of her. This was enough to make him an imaginary lover of a celebrated lady. As he moved around all over the city showing the magazine’s cover page to his friends, he turned himself into an advertisement. Another facet of his romantic self was seen in his deep infatuation with Nargis which started after his meeting with her in a studio where she had praised his poetry in highest terms. Here again, he thought he had found his love but that was not more than a mere fantasy. In the story of his long and short obsessions with young and beautiful ladies, we also come across his fascination for Lata Mageshkar and Shakeela Bano Bhopali which appeared and vanished with time.

The last episode in Sahir’s story of love and longing relates to Sudha Malhotra, the extremely talented celluloid singer. This was a story of genuine love for each other but was once again destined to end in disappointment. As social taboos could not be ignored at any cost, Sudha was betrothed and her wedding date was announced. This was precisely when some of Sahir’s friends organised an event one evening in his honour. In this mehfil of friends, Sudha too was invited. She joined the company of friends knowing quite well that this would be her last meeting with Sahir. In this special union of close friends, several singers sang his poems. When they asked Sahir to recite his poems, he chose to recite one of his most celebrated poems:

After Sahir finished his passionate reading of this poem, the audience appeared emotionally moved beyond all description. Faces turned sad, eyes went moist, and an unending silence prevailed. Interestingly, one of Sahir’s uniquely romantic poems of longing—mujhe gale se lagaa lo bahut udaas hoon main—was sung by Sudha Malhotra herself. With all his dreams and aspirations in love and life, Sahir turned into a myth in his lifetime. And remains so till this day.

Thursday, 14 May 2020

Love-life of Josh Malihabadi

Except for a few, Josh does not name all his beloveds by name but by alphabets. Was this an act of subterfuge, or a matter of social constraints that kept him from revealing identities? Again, we don’t have an answer because he alone knew why he did what he did. He only said that he clearly distinguished between love and lust and rushed to admit further that he surely fell prey to lust at times but got rid of it the very next moment. Of course, he did not want it to prevail over love.

Some of his stormy affairs that he chooses to mention by name are those with Miss Mary Ronald, Miss Glenzy, M. Begum, and R. Kumari. In the case of the last two, he does not spell out the M and the R and prefers to keep them under the veil. All the accounts of his love, irrespective of names, read like enticing literary narratives built carefully to engage the attention of his readers. He presents them with graphic details and takes the readers along with the sequence of events as they unfold with time.

When Josh tells the story of Mary, he presents her as one who was dying to entice him. He says that she called him to his quarters and created a condition where a physical relationship could grow and reach a stage of sexual encounter. He also does not shy away from saying that his father got furious on knowing about this and said he would allow him to marry her only if she embraced his faith. As it happens in romantic stories, Mary refused to do so. In a fit of desperation and anger, Josh revolted against her. He walked out of her house never to go back. In such a state, he even left Lucknow and shifted to Agra. As love stories do not end so abruptly, this too found a new turn. His luck brought him to see her after a year but this time he was meeting a totally dishevelled Mary. Unable to check himself, he embraced her passionately but she tried to disengage from him saying that in separation from him, she had become a victim of tuberculosis. She also added that after he left her, she gave birth to a baby girl who was exactly his image but the baby could not survive. A desperate and remorseful Josh arranged for her treatment but it did not help much. She was destined to meet her end soon, and she did.

Another episode in his love-life relates with Miss Glenzy. She was a medical doctor and was sent by his father to examine a girl and ascertain her puberty so that she could be married to Josh. Instead of taking leave after doing her job, Dr. Glenzy stayed back and met Josh. Josh tells us, as he told us in the case of Mary, that she too was enamoured by him. Unable to control her intense liking, she called him to her room and made obvious gestures that naturally pulled Josh towards her. As expected, this ended in sexual encounter. With this, the plot grew thicker. This time again, when his father came to know of yet another affair of the same nature, he grew angrier than before and gave him a tight slap. Although he warned Josh sternly against any further move towards her but that was too tough an admonishment for Josh to take. So, when the possibility of their getting into wedlock was contemplated finally, he posed the same condition that she should first embrace his faith. Glenzy was totally broke with such a condition coming her way. She met Josh’s mother, touched her feet and begged that she may be allowed to marry Josh. When his father appeared, she bowed down before him too and cuddled his feet. She implored as pathetically as she kept asking for Josh’s hand. Being a sympathetic man, he was moved by her passionate beseeching and agreed for her nikah with Josh. Unfortunately for both of Josh and Glenzy, the appointed day and time remained only an illusion. She suddenly collapsed and before she could be retrieved, she succumbed to death. This broke Josh once again but not for good.

There are many more stories that preceded and followed Josh’s affair with Mary and Glenzy. In all of these, he presents himself as the one sought after rather than the seeking one. In spite of this, Josh also emerges as one who remained sincere with each of his beloveds and gave himself completely to them without any consideration of the mundane kind. In spite of all the hurdles that Josh faced, he remained a sincere lover and a sympathetic human being. An emotionally honest Josh has remained an icon of love with a difference.

Heer Ranjha

While at home, Ranjha had a dream and in his dream he had the vision of an exceptionally beautiful girl. He was enamoured by her and wished to meet her. So, when he left his home, he decided to move towards Multan to seek solace from the famous five pirs and find the whereabouts of his dream girl from them. Wandering from place to place, he happened to reach a mosque where he thought of spending the night. To assuage himself, he played his flute there but the imam of the mosque objected to this saying that music was not allowed in Islam. When he offered his logic that music knew no religion and could assuage a suffering soul, the imam saw sense and allowed him to spend the night there.

Wednesday, 13 May 2020

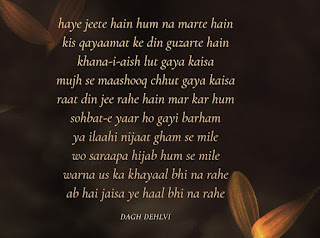

The love-life of Nawab Mirza Khan Dagh Dehlvi (1831-1905)

One has often heard that love is blind and that it brings only misery. If this be true, this must be true in the case of Dagh Dehlvi. Dagh was a man of colourful disposition and craved for the company of the beauteous beings. As his luck would have it, he came across a young and beautiful lady known as Munni Bai at the unique annual fair of Rampur appropriately called Benazir. Munni Bai was a courtesan and she had travelled all the way from Calcutta to Rampur to enjoy herself at the fair which promised impressive spectacles to its visitors from far off places. Dagh fell for her as he loved her looks and Munni Bai fell for him as she loved his poetry. Inflamed in love, Dagh expressed himself unreservedly in his masnawi Faryaad-e Dagh which has immortalised both Dagh and Munni Bai:

Another reason for Dagh to be enamoured by Munni Bai was that she too was a poet of considerable merit. Interestingly, this courtesan-poet chose “Hijab” for her pen-name which meant “veil” and a veil, as one knows, does not allow anyone to cast a glance at the face. Yet Dagh saw her, as did others, in great admiration. Hijab stayed for some time in Rampur but once the fair was over, she had to leave. She did leave indeed and left a lover behind pining for her. As they separated they took vows, as lovers do, to remain committed in their love and keep in touch through letters. Dagh recorded this moment:

Tuesday, 12 May 2020

The Love-Life of Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869)

Although Ghalib configured his love metaphorically, it is not difficult to recognise faces that wear the veil of his poetry. While some of them are imaginary, others are as real as life itself. We know that he was married to Umrao Begum, the thirteen-year-old daughter of nawab Ilahi Bakhsh and niece of the nawab of Ferozepur Jhirka. We also know that he fathered seven children but none of them could survive beyond a few months. It has been often said that he was unhappy in his married life but there are evidences to show that he cared for Umrao Begum although he was bitter with her for many other reasons. Indeed, Ghalib shared a richly ambiguous relationship with her knowing not how to fare forward. This is probably why he considered life as a term of imprisonment.

Not finding the desired gratification in the institution of marriage, men are known to have sought their pleasures elsewhere. Is it a matter of infidelity, one wonders. Some may say “yes” but Ghalib probably did not think so. And if he did, he did not how to resolve this dichotomy. So, whatever he did, he did only naturally and without much rationality behind them. There are two cases to mention here. He was enamoured by a coquettish singing girl but showed utmost poise in his relationship with her. Visiting the singing, or dancing girls, or even courtesans, was not supposed to be a demeaning act during those days. Indeed, men of high status visited them and enjoyed their company. One such girl whom Ghalib visited was known as Mughal Jaan and he was deeply fascinated by her.

Unfortunately for Ghalib, she was also the cynosure of a good looking, suave and a contemporary poet of great merit called Hatim Ali Mehr who also admired her and visited her as Ghalib did. Mughal Jaan did not hide her dual sympathies and she shared his liking for her with Ghalib. Ghalib, being Ghalib, did not burn in anger and did not think of him as a rival. None of the three knew, however, that God had a different design for them. Mughal Jaan did not live long enough to let this plot thicken. She passed away too soon in her life. Mehr was deeply aggrieved as was Ghalib but Ghalib showed the highest kind of courtesy in writing a note to Mahr to assuage him and to share his grief with him. Ghalib’s love for Mughal Jaan was of a rare kind; he was romantically disposed towards her but was painfully aware that his sympathies would not go too far. Mughal Jaan was both–Ghalib’s fantasy and impossible reality.

Human nature is also known to make peace with loss. So did Ghalib. After Mughal Jaan, his love-life did not reach an end. This time he got into contact with a respectable lady from a respectable family. This is said to have continued secretly as his shers during the period bear him out. This affair did not last long. He found another beauteous being yet again who would give all he wanted—emotional solace and physical contact. This lady was an admirer of poetry and poets and Ghalib undoubtedly was the one whose companionship any poetry lover would pine for. She used to send her ghazals to him for his opinion. This brought both of them closer to each other although she was a minor poet and Ghalib would not have otherwise drawn closer to her but for his amorous nature. Ghalib referred to her as the “Turk lady” and enjoyed her special companionship the most. Their affair went on secretly and reached a stage where every excuse would only bring greater damage to their reputation than repair it. Fearing the onslaughts of the society for doing an inexcusable wrong, the lady chose to sacrifice her life. This put Ghalib to great agony. The incident might have lost its fire with time but it remained fresh in his imagination. A ghazal he wrote subsequently with the radeef of “hai hai” is more expressive than many other of his ghazals. This ghazal is an epitaph for his “Turk lady”, as well as an act of love-sharing with her that shows Ghalib’s genuine respect for her. Unable to bear the loss, he fell ill and expressed his grief in the most poignant terms possible. Incidentally, this also happens to be one the best known ghazals of Ghalib.